They’re in control!

Though only four seasons in to Doctor Who‘s run, by the time of Ian Stuart Black’s “The Macra Terror” (Story Production Code JJ), one would be forgiven for thinking that the series has a limited number of stories to tell. The prior story, the Cybermen sophomore effort “The Moonbase,” plays as a virtual repeat of first Cybermen story, “The Tenth Planet,” with Kit Pedler writing both. Now we have Ian Stuart Black riffing on his favored theme, that of a hidden power secretly controlling people’s minds for some nefarious purpose, as last seen in “The War Machines.” Only this time, replace a self-aware computer in ’60s London with crab monsters in some future human colony, with a touch of the utopia hiding a deadly flaw (as seen in his “The Savages“) for good measure.

On the surface, it’s not a bad story idea to revisit, and the approach here differs from “The War Machines” in focusing on the dehumanizing force of brainwashing and subliminal messages rather than the dangers of technology run amok. Advertising jingles carry a strong propaganda message to the colony and play in the background even as the actors speak, suggesting that they are always playing, forcing happy thoughts into all of the colony’s inhabitants. As the leader of the colony states, they regulate their lives by music.

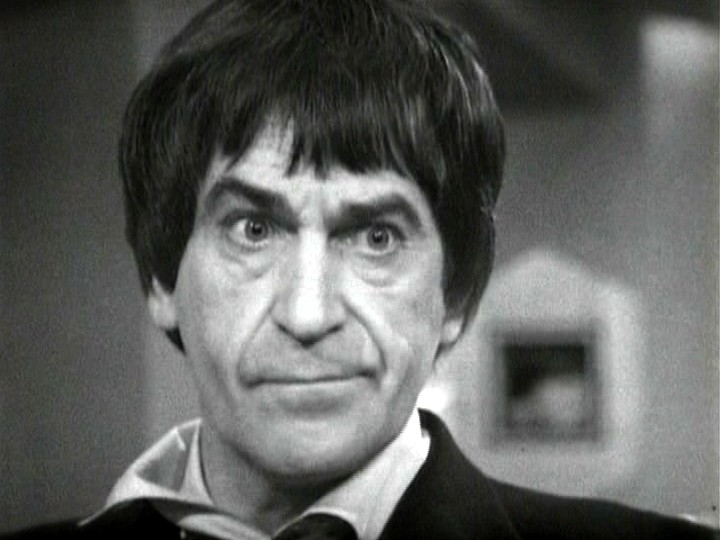

The Doctor and his companions arrive on this far-flung planet to inadvertently assist in the capture of a dissident from the unnamed colony, whose crime is twofold—he’s not happy, and he has seen something forbidden that he refuses to repudiate. The Doctor takes a liking to him immediately, while Ben and Polly just want to get the free shampoo and massage on offer as a reward for helping the colony capture this dangerous ne’er-do-well. Their glee at such services leads one to wonder if there’s a shower on board the TARDIS. But there’s a price to be paid for the spa treatment, as Polly soon finds out.

Yes, she’s seen the Monster-of-the-Week, the crab/insect creatures known as the Macra. Quite often, one mourns the loss of so much Second Doctor footage. Well, not so much here.