For the inaugural post in the new Table for One project, a series of wargame reviews with an eye towards solitaire suitability, I’m going back to the first wargame I ever played: Sinai (1973), by SPI. Then, as now, I tinkered with this operational level one-mapper on the various Arab-Israeli wars without benefit of an opponent. Unlike the last time, however, I sort of know what I’m doing this time around.

Playing a wargame sans opponent requires an understanding of how wargames work, and some thirty-odd years ago, first confronting this mass of paper and cardboard and rules, I had no idea at all how to proceed. But I was hooked nonetheless, captivated by the possibility of moving these variously colored forces across the stark buff-and-blue map.

Even then, as certainly now, I loved the idea of chrome, and the promise of a US expeditionary Marine force or a Moroccan mechanized battalion entering the fray made me determined to learn how to play wargames. I didn’t really succeed then, but mostly because I didn’t know how to play both sides at the same time.

It’s an acquired skill, this simultaneous solitaire, requiring both an uncanny impartiality and a willful ignorance of what the “other half” of your brain is planning. With years of playing face-to-face against an opponent under my belt, it’s actually rather easy to drop into this dual-mindedness. Sometimes your opponent knows what you’re going to do and will try to oppose it directly; sometimes, he or she doesn’t see it. You can tie yourself into knots trying to guess if your opponent knows what you know—that way leads analysis paralysis, a dreaded gaming disorder. You just have to take your chances to the best of your ability. Wargames are sufficiently complex creatures that you’ll often overlook a good move or clever feint until you switch sides and see clearly what you should have done. That little bit of uncertainty makes solo wargame play possible.

Still, some games provide a better solitaire experience than others, and in Table for One, I hope to look at games from a solo perspective and highlight what aspects of them make for good, or poor, single-player experiences.

Overview

Sinai: The Arab-Israeli Wars, ’56, ’67 and ’73

Simulations Publications Inc. (SPI), 1973

Designed by James F. Dunnigan

Sinai was released in two versions, as a boxed designer’s edition and in the infamous SPI flat pack with integral counter tray. My copy is the latter, complete with folded rules folio. Everything about the SPI flat pack, down to the cheap, poorly-molded d6, screams cost-savings, and the ability to simply drop in a new cover sheet under the flimsy plastic cover allowed SPI to push an enormous number of games out the door. SPI was nothing if not prolific; the contemporary management notion of “fail fast” seems tailor made for their way of business, leading to some remarkable successes at the price of a few less-than-brilliant games, all sent into the world at a breakneck pace—breakneck, at least, in comparison to today’s wargame publishing market, where most games are subjected to lengthy waits on pre-order lists prior to release.

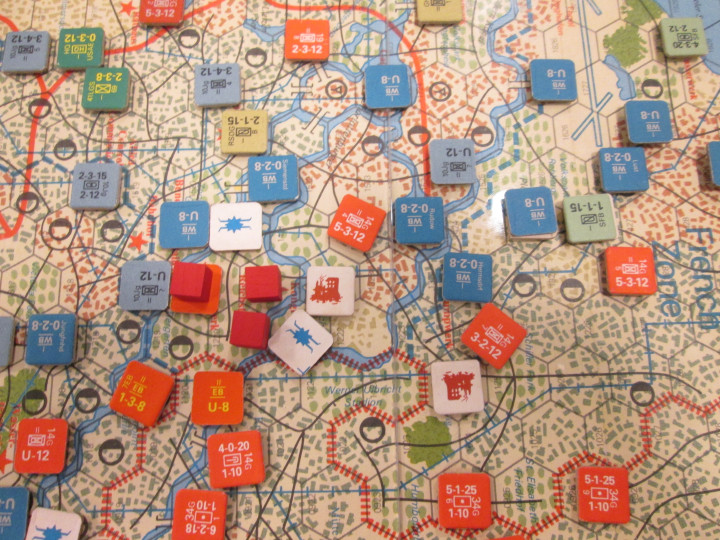

Sinai comes in as neither an overwhelming success nor a resounding failure. It’s a fairly bog-standard ’70s wargame, with locking zones of control and an utterly bloodless Combat Results Table. The single standard-sized map is awash in blue and tan, with a slightly confusing road network and terrain roster that variously exists depending on which scenario is being played. The 255 half-inch counters are front-printed only on decently thick cardboard, with crisp printing in a few colors that nevertheless allow for good differentiation between the multiple factions in play. One either deeply appreciates Redmond Simonsen’s Letraset skills or finds them bland; I fall firmly in the former camp. Indeed, the clean lines and contrasting colors of this game’s components, far more than the gameplay itself, helped draw me into this hobby all those years ago.

The counters in my copy suffered just the slightest bit of off-registration printing, leading to some counters with an off-color band on the bottom or side. The die cuts were good and well-centered, however, and the counters look quite tidy after a visit from a 2mm Oregon Laminations Counter Corner Rounder.

Order of battle research seems thin on the Arab side, with only a few units given specific designations; by contrast, the vast majority of pre-1973 Israeli units are delineated and set up in their historical starting locations.