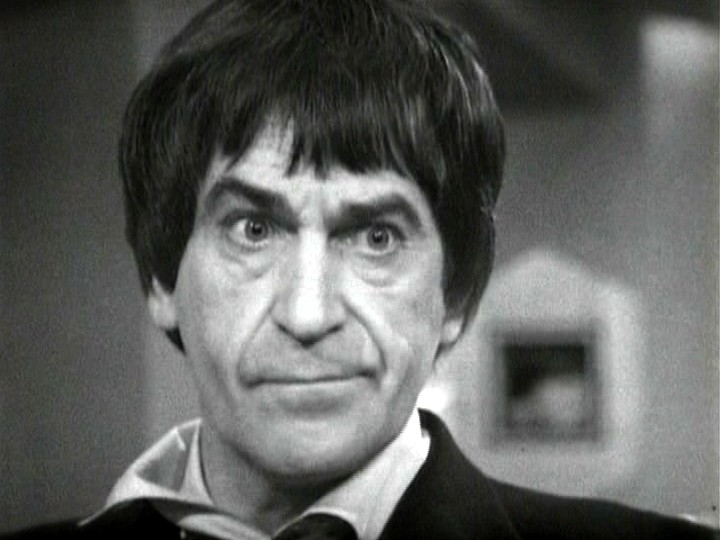

In many ways, Patrick Troughton is both the “missing” Doctor and the most important Doctor of them all.

When Patrick Troughton took over the role from William Hartnell in the famous dissolve shot at the end of “The Tenth Planet,” he proved that Doctor Who as a concept could last beyond the tenure of a single Doctor. A failure of the audience to embrace this change in actors—indeed, this change in the very nature of the character itself, from wizened curmudgeon to puckish raconteur—would have ended the series for all time. It is to Troughton’s credit that he succeeded quite resoundingly, becoming the Second Doctor, not the Final Doctor.

And yet, he’s nearly unknown to modern viewers of Doctor Who, perhaps remembered for his pipe flute and iconic showdown with the Cybermen on Telos but not recognized as the Doctor who fully advocated aggressive intervention when necessary to fight evil in all its guises, who allowed people to underestimate him (to their own chagrin and, often, peril), who managed to combine slapstick with seriousness. He’s merely that “other” black-and-white era Doctor, the one without the scarf or the car or the celery stick. It’s a status worth changing.

Patrick Troughton’s relative anonymity stems from the missing episodes. Though William Hartnell’s stories have sizable gaps in extant film copies owing to the BBC’s short-sighted policy of re-using admittedly expensive video tape, fully thirteen of Patrick Troughton’s twenty-one stories remain missing on film either in whole or in part. Modern viewers of Doctor Who have to work to experience the full adventures of this impish and inquisitive time traveller by seeking out the DVD compilations of the few remaining film trims from the “missing episodes” or listening to the recordings made by contemporary fans of the show who literally put a tape recorder microphone up to the television speaker and implored their family members to remain quiet during the sole weekly broadcast. Amazingly, enough of these tapes survived to enable restoration of all of Troughton’s stories in audio format, many of which were combined with film stills or animation to recreate the missing episodes to some extent.

Sadly, so much of Troughton’s strength as the Second Doctor comes from his non-verbal acting—innocent looks, sly glances, shrugs fraught with meaning—that the audio alone (even when paired with animation or stills) fails to convey much of the real story going on. Plot, after all, is only part of Doctor Who‘s appeal, and knowing that the fish people are being rescued from servitude matters less than how the Doctor behaves while rescuing them. Combined with an increasing emphasis on visual effects during the Second Doctor’s tenure, the lack of footage for so many stories reduces even the reconstructions to long periods of, well, silence, reducing Troughton’s missing stories to their basic narrative elements and robbing modern viewers of the full impact of Troughton’s expressive style.

Put frankly, these narrative elements don’t tend to flatter the Second Doctor. An overreliance on the foam machine and a tendency towards Grand Guignol-style acting by villains (and occasionally companions) tars many of Patrick Troughton’s stories, most of which are about the conquest of the Earth for unstated yet surely nefarious purposes. Gone are the long ruminations on the sanctity of the historical timeline; for the Second Doctor, it’s helicopter escapes and bazookas and mad mathematicians and underwater lairs and, yes, shrunken college students kidnapped by aliens on their way to Ibiza. When the Daleks do appear, twice, they squander their visceral appeal with half-hearted schemes that make hollowing out the Earth’s core seem ingenious by comparison.

The Cybermen come into their own as the Second Doctor’s true foe, edging out the Daleks (and their cantankerous creator) to become the go-to monster and villain with four stories of uneven quality across Troughton’s two and a half seasons. These are not the bio-existentially troubling Cybermen of “The Tenth Planet,” so recognizably human under their shimmering skin, but rather more fully metallic men bent on the narratively uninteresting aim of conquest. They gain features with each new appearance (never mind that the appearances are not in chronological order), ending in “The Invasion” with an arsenal of flame guns and death rays when either one would ostensibly suffice.

Attempts are made, moreso than during Hartnell’s seasons, at developing more recurring monsters, but with only minor success. The Ice Warriors, those reptiles from Mars, make their debut during Troughton’s era and were sufficiently popular to be brought back for a second outing, while the Yeti (furry robots, really) and their controlling Great Intelligence also make two appearances. The less said about the Quarks and Krotons, alas, the better.

For all the flailing about on the part of the writers and producers, though, there’s a special quality to Patrick Troughton’s time as the Second Doctor. He establishes the Doctor as not just a scientist, not just an observer, not just a moralist; the Second Doctor acts. Even when seemingly doing nothing, as his character is wont to do, Troughton imbues the Second Doctor with a vital energy, a purpose to the time and space travel. He refuses to allow evil to stand unchallenged, history be damned, and every successive Doctor, to a greater or lesser extent, owes this moral indignation at the prospect of evil triumphing to the Second Doctor.

Indeed, while before a tribunal of Time Lords in the finest of his stories, “The War Games,” he proclaims:

“All these evils I have fought, while you have done nothing but observe!”

This is the Second Doctor’s truest legacy. No future Doctor will merely observe.

Under Patrick Troughton’s watch, Doctor Who ceases to be about random excursions through time and space. Indeed, it’s barely even about time travel anymore. While canonic continuity remains an elusive (and, for the producers, not quite sought-after) target, the series now promises, week in and week out, to be about heroic conflicts with some malevolent force.

This vigor comes at a price, it must be said. The Second Doctor suffers very little, in comparison with the First Doctor. His goodbyes are minor and mostly unremarked, his failures likewise unremarkable and minimal in scope. No one is left to perish, no one to die, and he slips out at the end of most of his adventures, never to face the awful mess that remains in his wake. He is less human (even if not strictly not-human at this point) as a result, though much more of a hero. The companions with whom he travels—Ben, Polly, Jamie, Victoria, and Zoe—allow him to be brave and wise by example to them; indeed, the relative independence of Ben and Polly, holdovers from the First Doctor, sees them jettisoned once the audience can be fairly believed to have accepted the Second Doctor as the Doctor.

The Second Doctor sets the stage for all the Doctors to follow. They might be flighty or aloof, they might hew to a slightly different moral code, but they all act. For better or for worse (and usually for the better), they get involved in a manner, and with a sureness of purpose, that starts with Patrick Troughton. Without him, without the Second Doctor, we don’t have Doctor Who.

Post 52 of the Doctor Who Project